Verónica Gerber Bicecci. The Company. Translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney. NY: Sundial House, 2024. 200pages.

PART ∅

I come from an industrial town in the northeastern side of Mexico. Monterrey has been known for its–mythical–beliefs in hard-work and tales of progress. But lately, it has also become a synonym of air pollution, overpopulation, and corruption. Corporations have co-opted the “natural resources” (a discussion of the problematic view of nature as a “resource” should be addressed in another essay) with the aid of both the state and federal governments.

This is not an entirely new phenomenon. The Company (2021; 2024) highlights the historicity of the extraction of natural resources, establishing that there are “trends that began with the conquest and colonization of Latin America and Africa 500 years ago.” It then goes to explain that these activities “have reached unprecedented levels since the turn of the [21st] century, as capital scours the planet in search of speculative and productive investments in the context of overlapping crises: economic, financial, food environmental.” (179)

Although there seems to be a clear resolution on the effects of the contemporary human consumption practices, especially in richer territories, drastic climate actions appear to be widely unpopular; both the richer and poorer classes keep growing, disparately, and billionaires and corporations bank on the normalization of dire life conditions with–occasionally–the pretension of a transition to “cleaner energies” (it is disheartening that the mainstream conversations that acknowledge and propose actions against climate change can only propose other ways of maintaining consumption practices and not propose a reduction of them, which we desperately need as a measure to really combat the climate crisis).

How can we, as readers, pay attention to what really matters? Are we tired and overwhelmed by the constant lashes of reality? Is the hourly notification of every breaking news breaking anything but our spirits? I am a firm believer that this viscous reality can only be pierced by the joy of literature in its different forms, mediums, lengths, and languages. For the last decade, I have been obsessed with texts that have helped me to defamiliarize myself with reality and that invite me to seek other points of view. To decode and recode into a multiplicity of approaches. To, in sum, learn by unlearning.

In this vein, there hasn’t been a book I have spent talking about more than The Company. Or rather, La compañía, since before the translation landed on my hands, I was unable to share this insightful, inventive, and timely piece with the anglophone sphere. I have approached this text from different fronts, but more often than not I do it through affect. Verónica Gerber Bicecci’s literary artifice makes of this one a stimulating reading for speculation that, although the text is clearly set up in a specific region (Nuevo Mercurio, Zacatecas), it has afforded me ways to understand many other contexts, including mine.

PART A

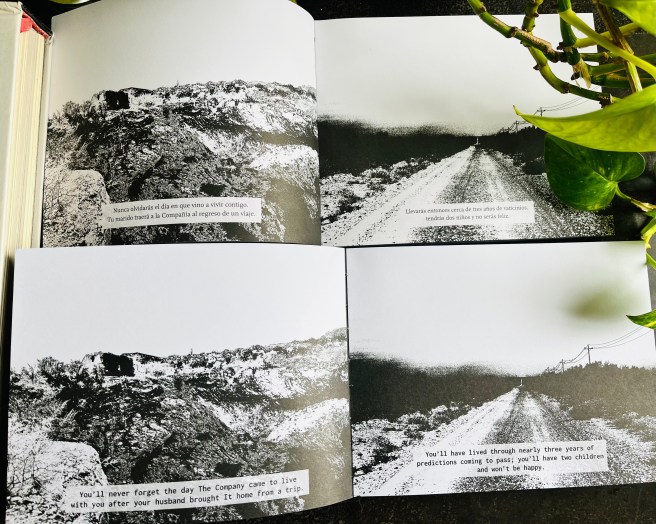

The Company is a two-set piece. The first section, or part A, is a rewriting of the short story “El huésped” [“The Houseguest”] by the Zacatecan author Amparo Dávila, originally published in 1959. Gerber Bicecci’s intervention consisted in substituting the characters of “the houseguest” and “Guadalupe” for “The Company” and “the machine”, respectively; changing the verb tenses into the future, and the narrative voice to the second person of the singular. Her rewriting is accompanied by two graphic components to compose a wall-story (as it was firstly introduced during the XIII FEMSA Biennial “We Have Never Been Contemporary”), some high-contrasted photographs of Nuevo Mercurio and graphic elements of Manuel Felguérez’s The Aesthetic Machine.

The story keeps the gloomy and sinister aura that Amparo Dávila’s original had, but instead of centering the critique only to the patriarchal structure that oppressed women, Gerber Bicecci’s version extends this critique to extractive endeavors and highlights the connections between extractive economies and systematic oppression towards women and other minorities. For The Company, much as for men raised and adapted by the patriarchal norm, the protagonist is nothing more than “a piece of furniture that one is used to seeing in a particular place, but which doesn’t register on the mind” (12). With the figure of the husband who invites the company as a guest and following Gerber Bicecci’s grammatical operations, the patriarchal pact is outlined as an active agreement between extractive capitalism, the State and the hegemonical and traditional role men have occupied in Mexican society.

PART B

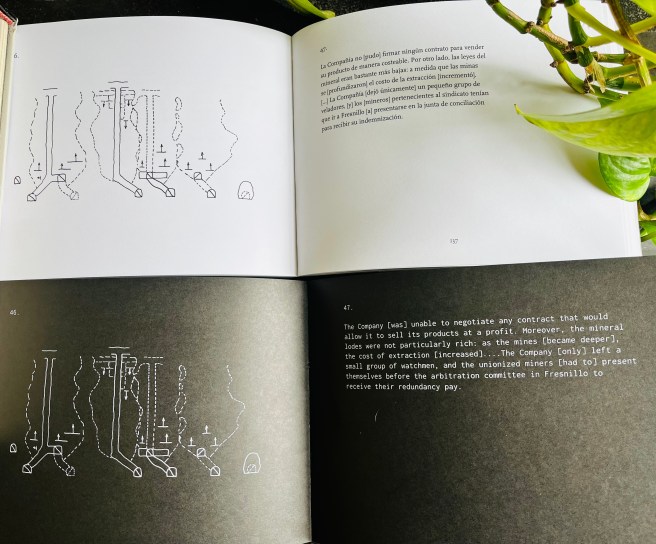

The second section, or part B, is composed of 100 archival vignettes: fragments of José Luis Martínez’s story “José Largo,” of conversations, academic and governmental research, testimonials of workers of the mine, geological studies, collected data on the effects of the exposure to mercury and toxic waste, maps of the tunnels, diagrams of the machinery, and images of bats. Together, these tiny pieces of partial histories construct a maddening picture of reality: for resources to be extracted, –human, non-human, communal, terrestrial, celestial–bodies will be caught in the crossfire.

The archive points towards class dynamics marked by greed and false hopes:

“Cinnabar is the mineral [from which] metallic mercury [is extracted]. In the past, ground cinnabar used to be sold in packets in hardware stores as [the pigment] vermilion…. ‘Look José,’ said Eusabio, ‘if there’s enough of this mineral in the place [you’re talking about], I swear on my mother’s grave that I’ll lift you out of poverty.’ That same morning, after loading…poncho, backpack, and [the] indispensable cask of water, they set off.” (96)

But much as the story presented in the part A does, it signals to the unevenness of the system for different subjects. Miners are welcomed with alcohol and a red-light zone, even before creating a water supply for the new settlement, positioning women as mere objects of consumption and satisfaction for the men who work in this mine. With this, the corporations make sure to keep the workers content enough to avoid any conflicts.

The companies take advantage of the precariousness in which many of their workers live and offer them cheap salaries and instant gratifications, without even acknowledging the danger that these zones of extraction represent for the workers and the communities around the mines. Not only that, but once they raise their voices and formal routes of action are taken, they disappear and evade their responsibilities altogether, leaving the communities in even worse conditions:

“We weren’t allowed to go there. They were afraid that there might be radioactivity. They said, ‘You’ll die, you’ll get cancer.’… Complaints were made but all that happened was that the gringos left, the mine closed and no one had any work.” (151)

PART 𓆙

Verónica Gerber Bicecci once again collaborates with the brilliant Christina MacSweeney, with who she has a steady literary kinship. MacSweeney has translated Empty Set (2015; 2018) and Migrant Words (2017), as well as other yet unpublished works and Gerber Bicecci’s website. In The Company, MacSweeney displayed a masterful craft by bringing this text into the anglophone sphere maintaining the ludic yet alarming gravitas of the text.

Verónica Gerber Bicecci once again collaborates with the brilliant Christina MacSweeney, with who she has a steady literary kinship. MacSweeney has translated Empty Set (2015; 2018) and Migrant Words (2017), as well as other yet unpublished works and Gerber Bicecci’s website. In The Company, MacSweeney displayed a masterful craft by bringing this text into the anglophone sphere maintaining the ludic yet alarming gravitas of the text.

Collaboration takes a central role in Gerber Bicecci’s writing. As Cristina Rivera Garza puts it in her epilogue to the book,

“[N]othing is hidden. Here–in contrast to the advice of the authors of Great Twentieth-Century Literature–everything is shown, seams and all. When passing from one page to the next, from one photo to another, it is clear that nothing we see is the result of mysterious, inexplicable, individual, authorial inspiration. Rather, it is the product of research and the selection of material form the world we share. All those materials are present, not so much for us to recognize as to recognize ourselves in them. Like any good disappropriationist, Gerber Bicecci repeatedly shows that a work is an appointment we–readers, material, and author–turn up to, if we wish at the same time. Here, we have stopped to look, to see, in the materiality of the book or the exhibition, in order to resolve and compare, interpret and define, as we come to articulate and know ourselves” (202)

These actions are full of intentionality, seeking to see literature not as a space of geniality and property, but as a place of creation that precisely depends on collaboration.

I have taught, discussed, and written about this text, simply because I believe it has so much depth and potential for insightful conversations. The Company has proven to be not only a literary object, but a pedagogical tool. For me, The Company is a tale of collaboration under the Anthropocene. Not only thematically, but also materially, Gerber Bicecci underscores the need for clear and even exchanges. In the story, we see the collaboration between a machine and a human:

“‘What can the two of us do alone?’ ‘Yes, we’re alone, but…’ There will be a strange glint in her eyes. You’ll be afraid but also filled with joy” (71).

The beautiful moment in which their fear is transformed into ecstatic complicity aims for more paths for collaboration, instead of individual actions.

Francisco Tijerina is a PhD Candidate in Hispanic Studies with a certificate in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Washington University in St. Louis. His research focuses on literary artifacts produced by women in contemporary Mexico and Latin America, extractivism, ecocriticism, climate fiction, ecofeminism, and animal studies. He recently co-coordinated a special issue on the conjunction between extractivism and gender for Pirandante and his article, “Technopoetics of the Anthropocene: Rendering Our Present through Echoes in Mexican Bots and Machines,” was published in the Bulletin of Latin American Research. He is the coordinator of the Diplomado de Actualización de Literatura Hispanoamericana of the Cátedra Carlos Fuentes at UNAM.

gratifying! 16 2025 Francisco Tijerina reviews ‘The Company’ by Verónica Gerber Bicecci (México/USA) stunning