Find me at the Sea

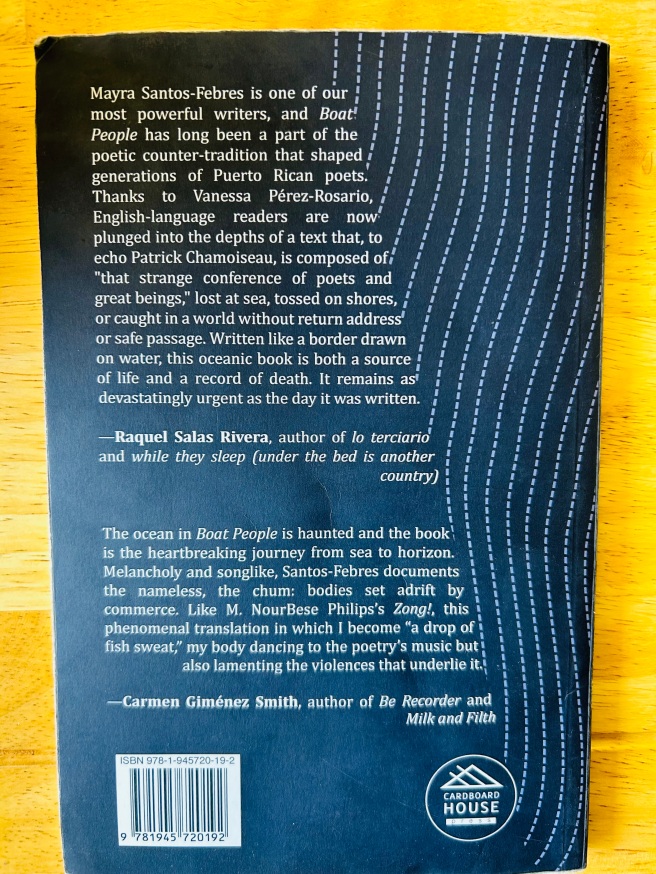

Mayra Santos Febres. Boat People. Bilingual Edition translated to English by Vanessa Pérez Rosario. USA: Cardboard House Press, 2021.

Poetics are a pathway to communality. It is the pathway to the possibility of codifying language, to communicate within centuries, to communicate with the Earth, even with the sea. Listening to the poetry of Mayra Santos-Febres means to listen to the ocean, its depths, and the many submerged voices of infinite underwater cities. The bilingual edition of Boat People, published in 2020 with translations by Vanessa Pérez-Rosario, delivers a haunting meditation on collective trauma from colonial and imperial relations that brings diaspora and migration to the ocean. Originally published in 2005, Boat People comes back after 15 years to remind us that the displacement of both the bodies of enslaved people and migrants persists today.

Poetics are a pathway to communality. It is the pathway to the possibility of codifying language, to communicate within centuries, to communicate with the Earth, even with the sea. Listening to the poetry of Mayra Santos-Febres means to listen to the ocean, its depths, and the many submerged voices of infinite underwater cities. The bilingual edition of Boat People, published in 2020 with translations by Vanessa Pérez-Rosario, delivers a haunting meditation on collective trauma from colonial and imperial relations that brings diaspora and migration to the ocean. Originally published in 2005, Boat People comes back after 15 years to remind us that the displacement of both the bodies of enslaved people and migrants persists today.

The sound in Boat People is more than the result of a poetic technique of rhythm. The sound embodies a voice, or voices, from the ocean depths. Within each verse extends an invitation to surrender to the sea… and to drown. A promise beneath the tide, that we will find a city free from the hunger and oppression that suffocates us in land.

air is lacking / wanting / so the journey goes on / to the illegal city in the ocean’s deep. / undocumented alveoli / explode in melancholy song. / air is wanting / but what’s different on the surface / if on the surface everything else is lacking / everything for the cooking pot and for the breast / for the pocket and the eyes […] / maybe in the ocean’s deep there’s an excess / of everything that suffocates here. (13)

The song is “melancholy,” yes, but why would that be a problem if in the ocean’s depths I find everything else?

Boat People is a collection of 20 untitled poems but unfolds as a single long poem of an epic journey that descends into the belly of the sea. It is an invitation to let us surrender to a submerged world that is upside-down. We do not find dead drawn people in this world. We find the bodies of our ancestors, our enslaved and undocumented migrants that are alive, waiting for us to hang out in a time of combites: “it’s time for combites in the deep” (67).

It’s in that “combite” that we can survive in communality. “Combite,” by the way, is a reference to Haitians that organize helping each other during work to the rhythm of music, with drums and chants of African traditions. It is a reference to communality. It’s time for us to commune with the ancestors, to organize and dance to resist the infinite oppression that suffocates. “It is time” to fight. “It is time” to resist.

The speaking sea of Boat People is a sea that seduces, that bewitches us to fall into a transoceanic conversation with Yemayá, whose voice echoes through the waves, invoking a spell of relationality. In invoking Yemayá, Santos-Febres engages with the spirituality of the sea, underscoring the importance of honoring the forgotten dead and acknowledging the intertwined fates of diasporic communities. To surrender to the ocean, to Yemayá, implies a reconciliation with ancestral roots. It also means to “hang out” (un jangueo) with the bodies of enslaved, undocumented, and forgotten ancestors.

Would you let yourself be drawn to join this jangueo? The ocean’s depth is as dark as the invitation to drown. The reconciliation comes with a sinister effect that goes beyond a simple jangueo, and yet, when I read Boat People, I desire to be at the sea, with its many voices, tides, and bodies, because I know that I will feel at home. I know that the confusion and seduction will end: “at last I can stop bewitching you” (73).

The poems connect slavery with the displacement of peoples in our neocolonial present in the Caribbean. In Boat People, the reader boards the poems like an open boat descending into the “abyss,” into the “womb” of a sea that establishes a certain «poetic of relation,» not only between the Caribbean and Africa but also among global diasporic experiences, migratory movements, paths of injustices, all submerged into the sea.

The «poetics of relation» in Boat People engages in a close dialogue with the section of the first chapter of Glissant’s Poetics of Relation, “Open Boat”. While reading Santos-Febres’ words, as we descend aboard the «open boat» and into the «abyss,» echoing Glissant’s relationality, we find a strong emphasis on a narrative continuity across four centuries. The boat and the abyss “free knowledge of Relation” (8), Glissant convinces us. That’s the knowledge that allows me to see the narrative continuity of Boat People, where the machinery of empire and capital, built through slavery, persists as the driving force of displacement in the present day.

There seems to be another force in Boat People, a submarine one the reunites those displaced in another city. This resonates in the exploration of the depths of the ocean—an underwater city of memories, bodies, and submerged stories— that remind us of the «Sea is History» of Derek Walcott.

the sea creates crystals confused with borders

refulgent things on foreign shores

far-flung we plunge yearning

following the rhythm of the waves

the beat of a whispering voice

mulata oh negress

come morenito mío

come dance here in the deep

no need to dim the lights

to speak softly.

there’s no hunger down here

and the dance never ends

all is supple

and inviting

it’s a question of letting go

let go completely (70).

In that invitation to dance in the deep, “come morenito mío / come dance here in the deep”, we find a seduction that we do not expect. We find a way of surviving that we do not conceive. Drowning to the ocean is confusing, yet revolutionary.

Drawing from the emerging fields of Archipelagic Studies, I read in Boat People a collection of poems that transcend simple representation to embody a fluidity of culture and identity, reclaiming the narratives of enslaved and migrant bodies consigned to the ocean’s depths.

The title itself talks about peoples who belong to the sea. We belong to the sea because “the sea remains” when our islands are destroyed “in half”: “the sea remains / behind his half island” (13). This motif, echoing Benítez Rojo’s «people of the sea,» serves as a call to consciousness, a reminder of the resilience of nameless migrants who crossed the waters. It is also a call to islanders who are witnessing the heaviness of the empire drowning our lands and contaminating our oceans and seas. There is a transoceanic poetic in these poems where Hawaii, Guam, the Canary Islands, the Philippines and the Caribbean coexists with other “small” islands. Islands become archipelagos of submarine connections. In this idea of fluidity in the depths of an ocean where identities are insufficient, Boat People challenges conventional notions of Caribbean identity, advocating for a broader conception rooted in diaspora and interconnectedness.

The title itself talks about peoples who belong to the sea. We belong to the sea because “the sea remains” when our islands are destroyed “in half”: “the sea remains / behind his half island” (13). This motif, echoing Benítez Rojo’s «people of the sea,» serves as a call to consciousness, a reminder of the resilience of nameless migrants who crossed the waters. It is also a call to islanders who are witnessing the heaviness of the empire drowning our lands and contaminating our oceans and seas. There is a transoceanic poetic in these poems where Hawaii, Guam, the Canary Islands, the Philippines and the Caribbean coexists with other “small” islands. Islands become archipelagos of submarine connections. In this idea of fluidity in the depths of an ocean where identities are insufficient, Boat People challenges conventional notions of Caribbean identity, advocating for a broader conception rooted in diaspora and interconnectedness.

Identity politics, while significant, are once again insufficient without a deeper interrogation of historical trauma and collective memory. In traversing the ocean’s depths, Boat People confronts the specter of violence. Yemayá seduces us to build an experience. A survival experience and survival demand more than existence. Yemayá demands a reconciliation with the past and a commitment to resistance. It is there where Yemayá’s seduction fulfills. It is there where our hunger and thirst ends.

Laura García García (Tenerife, Canary Islands 1990) is a doctoral candidate at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL). Her research explores the literary intersections of Caribbean studies and anti-colonial theories in archipelagic regions that have experienced the legacy of imperial rule. More precisely, she analyzes transoceanic relations between the Caribbean and the Canary Islands from an archipelagic perspective and the 21stCentury literary manifestations of these regions. Her work has been published in the Journal of Cultural Analytics and Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos. For El Roommate she has reviewed, in Spanish, a novel by Cirilo Leal