Ángela María Dávila. Fierce and Tender Animal / Animal fiero y tierno. Bilingual edition translated from the Spanish by Roque Raquel Salas Rivera. NY: Centro Press, 2024. 165pages.

In 2024, a powerful and beautiful animal was born, or rather re-born, in the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, the Fierce and Tender Animal. This book of poetry (in Spanishm Animal fiero y tierno) written by the Puerto Rican poet Ángela María Dávila Malavé (1944-2003) and first brought into light in 1977 by the queAse Press has long awaited its resurrection moment. And it was worth the almost half-century of hibernation, as the bilingual version brings this animal into an even more powerful form of life, a form that not only reflects the experience of its author, but also of one of her passionate readers and apprentices, the poet and translator Roque Raquel Salas Rivera (1985). In fact, to say the book has been hibernating is unjust. The limited number of copies of Animal fiero y tierno has been circulating for decades among Puerto Rican and other (not-only)-Caribbean students, intellectuals, poets, activists and compañerxs, from hand to hand, in the form of photocopies or pdf files. However, the publication of this bilingual edition in English and Spanish, makes this precious text accessible to speakers/readers of English or languages other than Spanish, be it Puerto Ricans in the diaspora, or bilingual devotees to Latin American literature, like myself, a student from Central Europe who only had the opportunity to read Dávila’s poems thanks to a Puerto Rican professor who treasured this book and shared it with us in a class on feminist writers. Reflecting on the twin version of the same poems now provides an even deeper experience of the mythical yet intimate universe of this fierce and tender text, a bridge to bringing her voice closer to my Czech ear. Just like Ángela María Dávila writes in the verses opening the first region of poems:

una cáscara dura

que detiene su límite

en la mano cercana

y en la lengua más próxima….

a hard rind

that detains its limit

in the nearby hand

and the closest tongue (16-17)

Is it a lizard, is it the ocean, is it my neighbor speaking? Could it be a rose? Or is it the hidden animal in me? When I read Ángela María Dávila’s poems the voices speaking to me are so elusive and yet so familiar. The “general voices.” They are whispering to us about the millenarian history of the species, of life on this planet and the power of kindness, they are roaring about the struggle of the oppressed and about anger and resistance, she reminds us of the beauty of little objects of everyday life, of things so simple as human touch. A woman – mother, lover, diva, activist, artist – is speaking, but also the many nameless and voiceless. Black female Boricua poet with a deep sense of humanism, inspired by her own personal experience and political sensibility rooted in a collective, relational and feminist consciousness and nurtured through her connections with revolutionary intellectual circles like the Guajana group.

Is it a lizard, is it the ocean, is it my neighbor speaking? Could it be a rose? Or is it the hidden animal in me? When I read Ángela María Dávila’s poems the voices speaking to me are so elusive and yet so familiar. The “general voices.” They are whispering to us about the millenarian history of the species, of life on this planet and the power of kindness, they are roaring about the struggle of the oppressed and about anger and resistance, she reminds us of the beauty of little objects of everyday life, of things so simple as human touch. A woman – mother, lover, diva, activist, artist – is speaking, but also the many nameless and voiceless. Black female Boricua poet with a deep sense of humanism, inspired by her own personal experience and political sensibility rooted in a collective, relational and feminist consciousness and nurtured through her connections with revolutionary intellectual circles like the Guajana group.

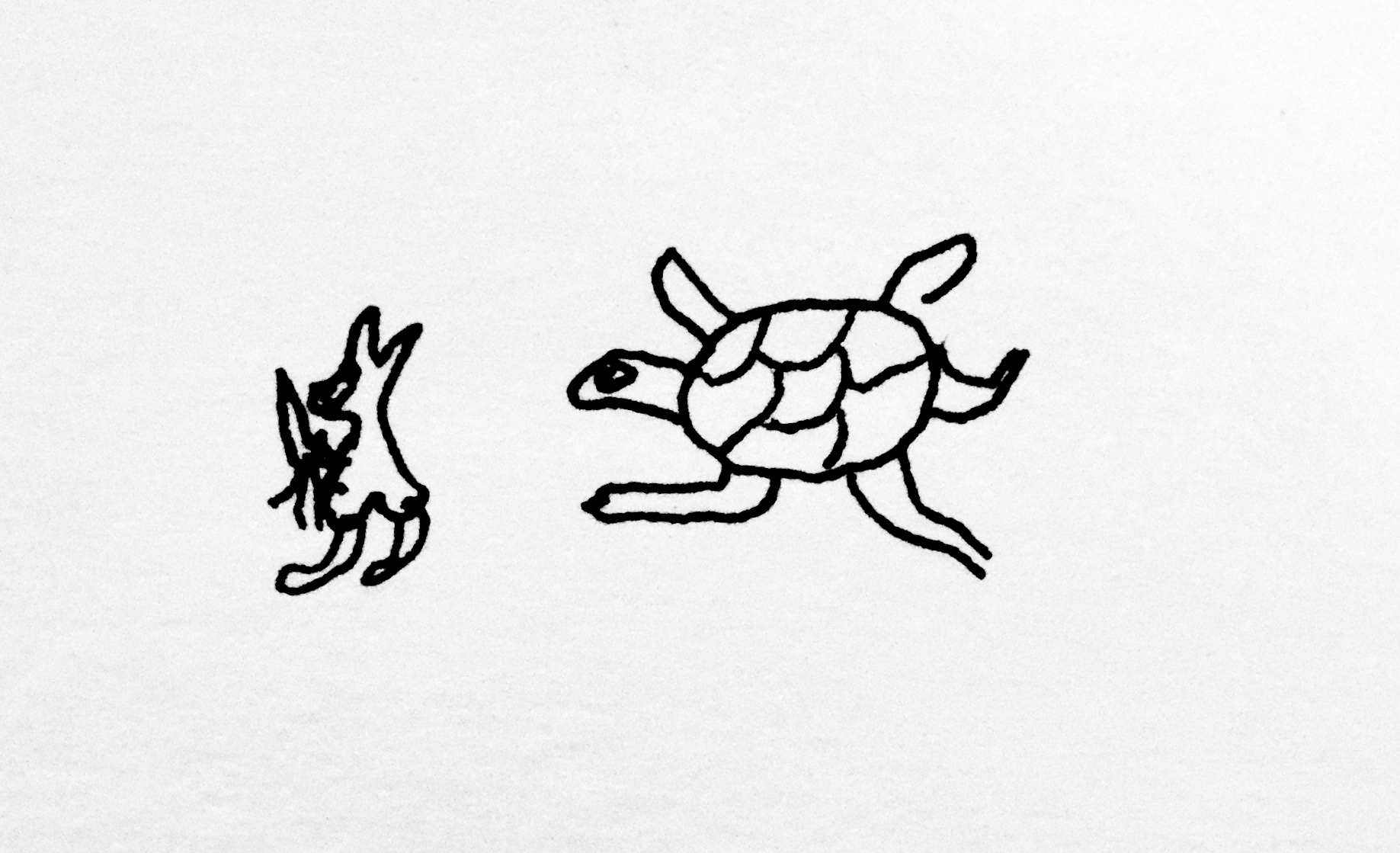

The format of the original Animal reveals the artistic freedom Dávila took in creating this subtle book, interwoven by numerous subtle messages in the form of drawings by the author, dedicatory notes, indications of year when the poems were written as well as the usage of different fonts, omitting of capital letters and diacritical signs. Not only the poems themselves but also the personal “visual voice” in which they are delivered are valued by many, and Salas Rivera reflects on that. The peculiar graphic aspect of the original and the rebellious orthographic decisions made by the author are preserved in the new bilingual edition, so the result is an almost-perfect mirror. The translator did make a change with respect to the graphic borders between the four regions into which the book is divided. While Ángela María Dávila includes drawings of a fetus at the end of each poem and each region, representing the book’ s conception as a womb, Salas Rivera’s edition includes vertical lines. Still, the little creatures so characteristic for this collection appear in parts where they accompany single verses.

And when I write “almost perfect”, it is to not undermine the translator’s work, which gives another unique and complex voice to this animal, while still being true to the original. Salas Rivera paid attention to the smallest details and did an exceptionally honest job interpreting Dávila’s notes, drawings and, of course, her metaphors, ambiguities and plays with multiple-meaning words. The translations are annotated by 67 notes by Salas Rivera, where he explains the decisions taken about words and clarifies the nuances and particular local meanings of specific expressions. These notes provide a valuable insight into Dávila’s poetic world and her social context and to the translator’s work.

In the “self dedication” [«autodedicatoria»] Ángela María Dávila writes:

“las voces generales, al acecho

me gritan por la calle sobrenombres:

‘no eres tú la amorosa

que busca entre las bestias

la fuente de su estirpe?’”

…and Roque Raquel Salas Rivera translates:

«general voices, prowling

scream sobriquets at me in the street.2

‘aren’t you the loving one, who slowly3

seeks among the beasts

the source of her lineage?’”

Salas Rivera includes two notes within five verses. It is not the case of all poems, but we can see that he is thinking about the slightest detail that could impact the interpretation. In this self-dedication Dávila defines her position as a poet among souls and entities. Within (against?) the heritage of injustice and suffering, she seeks love and kindness through poetry.

In the translator’s note on Fierce and Tender Animal Roque Raquel Salas Rivera writes: “Through this translation I became a translator” (129). This long translation project that took ten years of work has played its role in Salas Rivera’s formation as a poet, as a translator and as a trans man in a transphobic world. On the path to identitarian and poetic discovery, Dávila’s matrilineal discourse presents a liberating counter-narrative in the way of poetic imagery of continual self-displacement, re-invention and self-identification with the lineage of subaltern voices, as Salas Rivera writes in an older review of Animal fiero y tierno published on the web Operating System.[1] I am not going to comment more on Salas Rivera’s reflection on the translation/creation process. It is included in the bilingual version of Fierce and Tender Animal, and I believe that it reveals the personal and poetic motivations, steps and discoveries of this journey exactly as he wants to share them. Today a renown poet, editor and translator with several literary awards, Roque Raquel Salas Rivera had taken the time to mature with this collection of poetry and has delivered a version of Animal that proves not only his talent, but also his profound and personal connection with Dávila’s works. The book I am holding in my hands today is a result of thorough study and deep understanding of the author’s circumstances and callings, which would not be possible without making an extra step to meet the Dávila Malavé family. Thanks to the collaboration between Salas Rivera and Dávila’s relatives, Fierce and Tender Animal is more than a bilingual book of poetry. It reveals a part of the poet’s personal archive including photos of original hand-written drafts, unpublished versions of poems with errors, corrections, drawings and notes as well as photos of Ángelamaría Dávila in different life stages.

The legacy of this Boricua poet and multifaceted artist is undoubtable in Puerto Rico as evidenced by the lineage of Dávila’s disciples, in the literal or metaphorical sense of word, like Mayra Santos-Febres (the author of the blurb on the back cover), Mara Pastor, or Luis Othoniel Rosa, whose literary work shows the influence of Dávila’s poems and political attitudes she embodied. They are the brood of the matrilineal genealogy Salas Rivera writes about. And now he sums his voice to allow the animal to circulate among a new generation of readers.

The legacy of this Boricua poet and multifaceted artist is undoubtable in Puerto Rico as evidenced by the lineage of Dávila’s disciples, in the literal or metaphorical sense of word, like Mayra Santos-Febres (the author of the blurb on the back cover), Mara Pastor, or Luis Othoniel Rosa, whose literary work shows the influence of Dávila’s poems and political attitudes she embodied. They are the brood of the matrilineal genealogy Salas Rivera writes about. And now he sums his voice to allow the animal to circulate among a new generation of readers.

Ángela María Dávila honors her predecessors, poets and activist such as Julia de Burgos, César Vallejo or Lolita Lebrón in her poems. Roque Raquel Salas Rivera’s Fierce and Tender Animal presents a tribute to Ángelamaría Dávila. This is a poignant reading, where the mythical and the intimate intertwine to give light into a new affect that, until this book, had remained nameless.

Let us finish by sharing with the readers, Dávila’s classic prophetic poem, «facing so much vision», translated by Salas Rivera, followed by the original in Spanish, “ante tanta visión”.

«facing so much vision of history and prehistory,

of myths,

of half–or quarter–truths,

facing so much self-dreaming, i saw myself,

the light of two words took off my shadow:

sad animal.

i am a sad animal standing and walking on a globe of earth.

the animal part i say with tenderness,

the sad part i say with sadness,

as is only right,

the way they always teach us the color grey.

an animal that speaks

to tell a similar animal its hope.

a sad mammal with two hands,

deep in a cave thinking of the coming down,

with a clumsy infancy, oppressed by things so foreign.

a small animal on a beautiful ball,

an adult animal,

a female with her brood,

that sometimes knows speech,

and would like to be

a better animal

a collective animal

that grabs sadness from others like shared bread,

and learns to laugh only if another laughs

– to see what it’s like –

and knows how to say:

i am a sad, hopeful animal,

i live, i reproduce, on a globe of earth» (27).

ante tanta visión de historia y prehistoria,

de mitos,

de verdades a medias – o a cuartas –

ante tanto soñarme, me vi,

la luz de dos palabras me descolgó la sombra:

animal triste.

soy un animal triste parado y caminando sobre un globo de tierra.

lo de animal lo digo con ternura,

y lo de triste con tristeza,

como debe ser,

como siempre le enseñan a uno el color gris.

un animal que habla

para decirle a otro parecido su esperanza.

un mamífero triste con dos manos

metida en una cueva pensando en que amanezca,

con una infancia torpe y oprimida por cosas tan ajenas.

un pequeño animal sobre una bola hermosa,

un animal adulto,

hembra con cría,

que sabe hablar a veces

y que quisiera ser

un mejor animal.

animal colectivo

que agarra de los otros la tristeza como un pan repartido,

que aprende a reír sólo si otro ríe

– para ver cómo es –

y que sabe decir:

soy un animal triste, esperanzado,

vivo, me reproduzco, sobre un globo de tierra» (26).

Martina Barinova (Prerov, República Checa, 1990) terminó su maestría en Literatura Latinoamericana en la Universidad de Nebraska-Lincoln en mayo 2017 con una tesis sobre la música rock en Nicaragua. En la actualidad estudia en el programa doctoral del departamento de Literaturas romances en Palacky University en Olomouc, República Checa mientras trabaja como maestra. Su proyecto doctoral se titula Paisajes naufragados, pueblos rescatistas: las poéticas de querencia en la obra de Marta Aponte Alsina y Josefina Báez. Para El Roommate ha reseñado a las autoras Josefina Baez , Samantha Schweblin, Fernanda Melchor , Guillermo Rebollo Gil y Sayak Valencia, Chiqui Vicioso , Lola Arias, y a Marta Aponte Alsina.

[1] Salas Rivera, R. “Raquel Salas Rivera on Ángela María Dávila’s Animal fiero y tierno” In The Operating System. April 2017. Accessed 25/01/2025.

https:// http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/6th ANNUAL NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: DAY 9 :: RAQUEL SALAS RIVERA ON ÁNGELA MARÍA DÁVILA’S ‘ANIMAL FIERO Y TIERNO’ – The Operating System and Liminal Lab

Un comentario sobre “Martina Barinova reviews a cult classic by Ángela María Dávila translated by Roque Raquel Salas Rivera (Puerto Rico)”