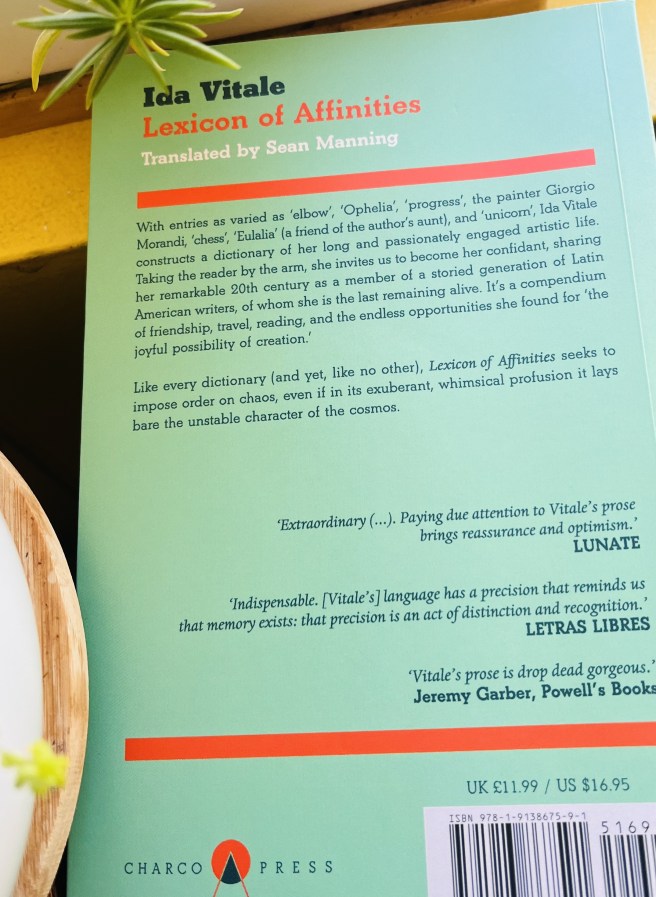

Ida Vitale. Lexicon of Affinities. Translated by Sean Manning. Edinburgh: Charco Press, 2025. 231 pages

0.

We can read the entry about “Boredom” in this book as a kind of autobiography, as if answering the question about what kind of mind ends up writing a book as strange as this. There, Ida Vitale insists that “she is not unacquainted with” those rare beings that never experienced a minute of boredom in their childhoods. The author cuts with precision (and precision is the art of this book) the mold of these “overwhelming, indulged individuals who enjoyed the proximity of an abundance of adults, multiple or in turn, occupied in entertaining them with the patience of the pedagogical vitality” (21-22). Then the entry has the inevitable Beaudelairian turn of the screw with the trope of boredom becoming a goddess of creation, the “mirage in the desert”, the “imaginary waters”. And it is a fitting move, paying homage to a very singular literary tradition. But I am much more interested in the experience of these individuals the poetic voice is “not unacquainted” with, because in that description we might find the key to the entire book. A sort of joy, an abundance of attention that nurtures a way of looking at the world with precision, a praxis of attention, maybe a childlike look, that makes the ordinary seem so interesting.

We can read the entry about “Boredom” in this book as a kind of autobiography, as if answering the question about what kind of mind ends up writing a book as strange as this. There, Ida Vitale insists that “she is not unacquainted with” those rare beings that never experienced a minute of boredom in their childhoods. The author cuts with precision (and precision is the art of this book) the mold of these “overwhelming, indulged individuals who enjoyed the proximity of an abundance of adults, multiple or in turn, occupied in entertaining them with the patience of the pedagogical vitality” (21-22). Then the entry has the inevitable Beaudelairian turn of the screw with the trope of boredom becoming a goddess of creation, the “mirage in the desert”, the “imaginary waters”. And it is a fitting move, paying homage to a very singular literary tradition. But I am much more interested in the experience of these individuals the poetic voice is “not unacquainted” with, because in that description we might find the key to the entire book. A sort of joy, an abundance of attention that nurtures a way of looking at the world with precision, a praxis of attention, maybe a childlike look, that makes the ordinary seem so interesting.

1.

An unnecessary masterwork – Lexicon of affinities has the form of a dictionary, a lexicon, but all entries are quite unique, sometimes poems, sometimes memories, sometimes essays, sometimes fiction, sometimes it’s the name of a writer, sometimes the memory of a book read a long time ago in a life dedicated to reading voraciously. The book wants you to pick it up and open it in any random page to find an illumination. I’m gonna do it right now… I randomly open the book. It’s page 210. It is an entry on “unpredictability”. I read “Happy are the unpredictable. They will be the hell of others”. The reader can read this either as reproach or an ode; either as the annoyance of the unpredictable, or as a song to their courage. It is up to the reader. It is the kind book that demands that participation by the reader. The reader must do something with it for it be amazing. It does not have the fatality of masterworks, of classics in which each combination of words seems destined to have happened, to uphold a perpetual admiration. This is an unnecessary masterwork. We did not need this book. It was not destined. But it happened. And it demands the creativity of the reader to turn it into a masterwork.

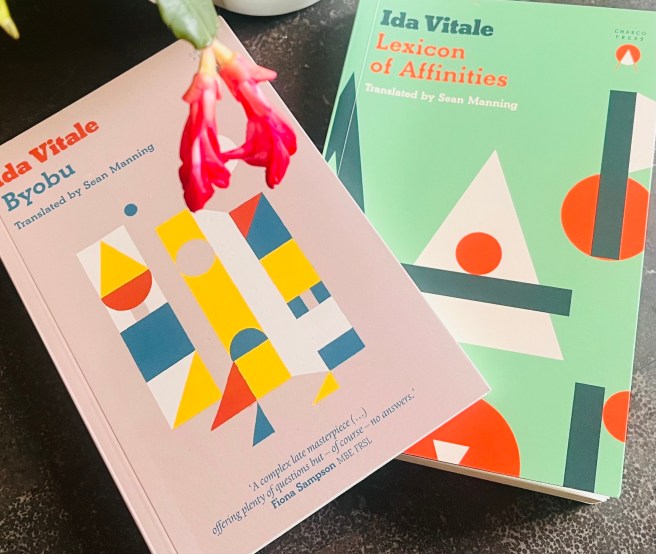

And perhaps Lexicon of affinities (first published in 1994, re-edited in 2006 and only now, in 2025, translated into English by Charco Press) can be considered part of a great trilogy with El ABC de Byobu (2004), also recently translated by Sean Manning for Charco Pres as just Byoubu (2021) and De plantas y animales (2003). Together, those three books compose a sort of chaotic galaxy of poetic affinities in which the autobiographical counterpoints the encyclopedic. Together, those three books has attracted a strong following of very peculiar hardcore readers in Uruguay in particular, and across South America.

And perhaps Lexicon of affinities (first published in 1994, re-edited in 2006 and only now, in 2025, translated into English by Charco Press) can be considered part of a great trilogy with El ABC de Byobu (2004), also recently translated by Sean Manning for Charco Pres as just Byoubu (2021) and De plantas y animales (2003). Together, those three books compose a sort of chaotic galaxy of poetic affinities in which the autobiographical counterpoints the encyclopedic. Together, those three books has attracted a strong following of very peculiar hardcore readers in Uruguay in particular, and across South America.

The translator into English, Sean Manning, shares the precision of the author. He is “not unacquainted” (this is a Borgesian turn of phrase) with the poetic richness of the life of the author. It is simply a masterful translation by a most gifted translator of great contemporary experimental Latin American literature (he has translated books by authors by Ricardo Piglia, Edouard Glissant, Eduardo Lalo, Diego Vecchio and Azahara Palomeque)

2.

In the entry about “recollection” (188), Vitale (with Manning) reflects on those memories that seem to disrupt the iron-clad of destiny, the memories that “do not appear to have the fatality of the past behind them”. These are most important recollections precisely because of what they disrupt; “the real pillars of our existence”. They do not produce reflection, the author tells us, but rather, they push us to invention. “Continuity with no beginnings” says Vitale. Time is no longer a tomb when these memories possess us. Time reveals itself in another way, no beginnings, no endings, no linearity. The world no longer seems destined towards catastrophe. And yet, by the end of the entry, another turn of the screw. These recollections are so hard to retain, like dreams, the author tells us. Perhaps that is why we write, for these disruptive recollections. Therein lies the power of this book. To retain their “inexplicable generative power”.

3.

“But a song is both a river and a net” – The very first page of the book, the “Statement of intentions”, is a literary miracle. The first sentence says: “This world is chaotic and, fortunately, difficult to classify”. In that adverb, “fortunately” (also a Borgesian turn of phrase), we find the first expected argument for the encyclopedic form of the book; the arbitrariness of the alphabetical form as a gift, randomness as a virtue, which is also an homage to a particular tradition of anarchist poetics, an homage again to a trope. By the end, however, we have a turn of the screw (again), away from that trope, and this time it is a poetic flight about words, about the agency of words in open rebellion against the law of inertia:

“Words mutually frolic, conspire, float, they are suicidal, dynastic, migratory, their every roar far from inertia. They do not expect us, ephemeral, standing on the wayside, to think them eternal, or that we can, ignorant of where we are, know our eventual destination following their lead. They are content if we, obeying some of their intentions, avail ourselves of what they propose, commensurate with our thirst and our glass” (page 1).

There is a contradictory obedience here to the unruliness of words; a minimal expectation, yet there; words expect something from us.

4.

“Words are nomads; bad poetry renders them sedentary” (page 180, from the entry on “poetry”)

5.

And since beginnings and endings only truly exist in literature, let’s turn to the end of the book, without quoting, without revealing. There are two endings. The first, an expected one, once again paying homage to a particular literary tradition, on the trope of the “warnings of humility” (masked in the commentary of two other literary traditions, the nature mortes and the zuihit su). In this first ending on the last entry (page 230), Vitale acknowledges how our “proper position in the world” is but a tiny land nurtured by “the prodigious creative joy of others”. All our individual creativity being just the result of a creative collective joy that came before us. I believe that this “positioning” is quite political. The revolutions that could take place if we truly acknowledge that any little moment of creative joy we have experienced has been the result of generations of struggles that came before us.

But as if this ending was not enough, there is another one, an ending without an entry, another turn of the screw (and by now the reader should know that the “turn of the screw” is very much a Uruguayan trope too, famously remembered in that novel by Juan Carlos Onetti, Los adioses, that “one-ups” Henry James famous novel, Another Turn of the Screw, which again makes us wonder, oh why is Uruguayan literature so incredible, per capita, at least for this reader, the strangest national literary tradition in the planet, with singular poetic voices like Felisberto Hernández, Marosa di Giorgio, Mario Levrero, Onetti, and yes, Ida Vitale). In the last page of the book a fantastic creature re-emerges, a “unicorn”, which was an entry before in the book, in the form of a sonnet, and now looks back at us with belief. The unicorn believes in us. Go read it and find out, because in that short poetic ending we might just find…. well, at least this reader, has found, the just poetic encouragement for the present desert of reality.

Luis Othoniel Rosa (Bayamón, Puerto Rico, 1985) is the author of the novels Otra vez me alejo (2012), Caja de fractales ( 2017), and Down with Gargamel! (2020). He is also the author of the bilingual collection of poems, Sadness, the Fury / Triste la furia (2025), the bilingual artisanal book, Calima (2023) , and the scholarly book Comienzos para una estética anarquista: Borges con Macedonio (2016; 2020). His long utopian novel, El gato en el remolino / The Cat in the Downward Spiral is forthcoming in 2026 in simultaneous editions in English and Spanish. He studied at the university of Puerto Rico and earned a Ph.D. for Princeton. He is editor and founder El Roommate: Colectivo de Lectores and founding memeber of The LOUDREADERS Trade School. He is the associate director of the Institute for Ethnic Studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. For El Roommate he has reviewed the books by the authors: Michelle Clayton, Raúl Antelo, Lorenzo García Vega, Margarita Pintado, Rafael Acevedo, Mar Gómez, Isabel Cadenas Cañón, Romina Paula, Mara Pastor, Julio Meza Díaz, Sergio Chejfec, Balam Rodrigo, Juan Carlos Quiñones (Bruno Soreno), Sebastián Martínez Daniell,Colectivo Simbiosis Cultural y Colectivo Situaciones, Margarita Pintado (¡otra vez!), Ricardo Piglia , Francisco Ángeles, Julio Prieto, Julio Ramos,Federico Galende, Julio Prieto (¡otra vez!), Áurea María Sotomayor, Noel Black, Marta Aponte Alsina (varios que se pueden encontrar en este Dossier), Naomi Klein, Mara Pastor (otra vez), Nicole Cecilia Delgado, Cristina Rivera Garza, Carlos Fonseca, Luis Moreno Caballud, Margarita Pintado, Raquel Salas Rivera , Joy Castro , Sebastián Martinez Daniell, Jeff Lawrence and Julio Ramos (again)

Un comentario sobre “Luis Othoniel Rosa reviews ‘Lexicon of Affinities’ by Ida Vitale in the translation of Sean Manning (Uruguay)”